If you Google search “Longest Night” and are persistent enough, making your way past sites like a Netflix series about armed invaders trying to abduct a serial killer from a psychiatric prison, past a novel about a nuclear accident, past sites about a video game and other products, you will eventually find that Longest Night also refers to a national memorial event held every December 21st.

The Longest Night, held on the winter solstice, the longest day of darkness in the year, is to remember the people who died in the past year while homeless.

It’s not clear exactly how many people die homeless each year in America. In the first ten years of Longest Night memorial events that my colleagues and I held in St. Louis starting in 2004, we read of the names of 233 people who died homeless in St. Louis—and the numbers grew greater in following years.

Similar events are held in hundreds of communities nationwide and one national organization estimated an average of 13,000 deaths of homeless people each year. Causes of death vary widely, including from freezing on the streets, to homicides, suicides, drug overdoses, and medical conditions complicated by a lack of adequate care.

While the exact number of deaths is unknown, what is clear is that far too many people are dying on America’s streets and in shelters.

No one should have to die homeless in America.

And for that matter, no one should have to live homeless in America, either.

Photo by Jon Tyson, Unsplash

And yet each year, thousands of people die homeless at a mortality rate three-to-four times the housed population and on average 28 years younger.

Further, more than 500,000 people are homeless in America even in the middle of winter, and it is likely that over the course of a year at least two million people are homeless.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

Effective Strategies Can End Homelessness

But to change the reality of people living and dying homeless, we need to advocate socially and politically for the effective and cost-effective strategies that have been shown by scientific research to end homelessness.

Various programs and services end homelessness, including:

- Affordable housing initiatives, including for persons with special needs. For example, the Housing First approach, which emphasizes rapid housing coupled with supportive services and financial management for rent, is effective for helping chronically homeless individuals into stable housing.

- Rapid Re-Housing, which provides short-term rental assistance and services to help people get quickly back into housing and prevent long-term homelessness.

- Assertive Community Treatment, a community-based mental health service which my colleagues and I adapted for homeless people with serious mental illness, is also highly effective for ending homelessness.

- Community-based substance abuse treatment services, like Community Reinforcement Approach, is another program which my colleagues and I again found positive research data for ending homelessness among people with alcohol and drug disorders.

These approaches are not always immediate, quick-fix solutions, especially for people for whom the streets and shelters have become a de facto way of life. People who are homeless often have multiple experiences—e.g., paranoid delusions, addictive behaviors, a long history of being abused and let down, behavioral patterns that help them survive on the streets but are counterproductive to stable housing—that can make the transition from homelessness to housing challenging.

But when coupled with outreach and engagement approaches that are person-centered, caring, patient, and practical, the vast majority of homeless people—even those with severe illnesses—can be assisted into stable and permanent housing.

Again, a number of research studies show that these and other programs end homelessness.

A Problem of Scale

The problem is not that we don’t know how to end homelessness.

Rather, it’s simply that we are not providing these services to fit the scale and magnitude of the number of homeless people in America, which is a failure of governmental policy.

Take Seattle as an example. Under a new mayor, the city has developed a homelessness action plan that is fairly progressive and ambitious for a local government. Seattle’s plan calls for 2,000 units of shelter and housing by the end of 2022.

That’s a start, but here’s two problems:

- The 2,000 units are less than 20 percent of the number of people homeless on a single night, and less than 5 percent over the year

- Shelter is not permanent housing. It still perpetuates homelessness.

Similarly, California’s city and county requests for $1 billion in state funding to reduce homelessness planned only for a 2 percent reduction in homelessness over four years—a very low bar that some local governments could not even agree to meet.

This dearth of resources, of failing to match the scale of the problem, is the main driver as to why people continue to live and die homeless.

Compare the low level of resources to the scale of the homelessness problem to other areas of public policy where instead of scarcity we have funded huge excesses in resources compared to need. For example, the United States has about 5,400 nuclear warheads—or about 36 times more than what is needed for the country to even survive a worst-case war scenario. Meanwhile, Congress just approved a defense spending bill for $45 billion more than the President and the Pentagon requested.

Why Not End Homelessness?

Many local efforts are now focused on cleaning up unsightly images, such as tent encampments and lines of broken-down RVs providing makeshift housing.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao, Unsplash

In short, many communities seem increasingly tired of the homeless.

But instead of being tired of the homeless, we should be tired of homelessness.

We have the know-how to end homelessness.

So, why don’t we provide the resources needed to end homelessness?

Three factors, which are interrelated, seem to be major reasons.

One, most people don’t really know people who are homeless, at least not in a deep or a holistic way.

Instead, we often make judgments about homeless people from limited information, from a distance, or from chance encounters.

For many, information about homelessness often comes from experiences like seeing unsightly tents lining an urban freeway, or being asked for money while walking to a restaurant, or hearing news reports about a peace disturbance at a homeless encampment.

Often we only briefly glimpse the person sleeping on the sidewalk under flattened cardboard or the disheveled individual, his back against a wall, while we walk past, trying to avoid eye contact. (Forty years ago a homeless told me that the worst thing about being homeless was not trying to figure out where you were going to get food or sleep that night but instead “having people walking past you on the street and look right through you as if you don’t exist.”)

Two, we often don’t understand the underlying causes that create and sustain homelessness. Instead, we sometimes blame homeless people for their homelessness, assuming they are lazy and don’t want to work, or that they simply choose homelessness.

Causes of Homelessness

The causes of homelessness are multiple and complex.

They include social conditions, like the lack of affordable housing (which helps explain why high-rent areas like New York City and West Coast cities have the highest rates of homelessness). Affordable housing is even more difficult to come by for persons who work at the low-end of the pay scales (can you imagine supporting yourself and your family at minimum wage?), and for individuals with disabilities.

The lack of adequate health and support services, especially for mental health and substance abuse disorders, is another major social factor.

And racism is undoubtedly a factor, as persons of color are greatly overrepresented among homeless people.

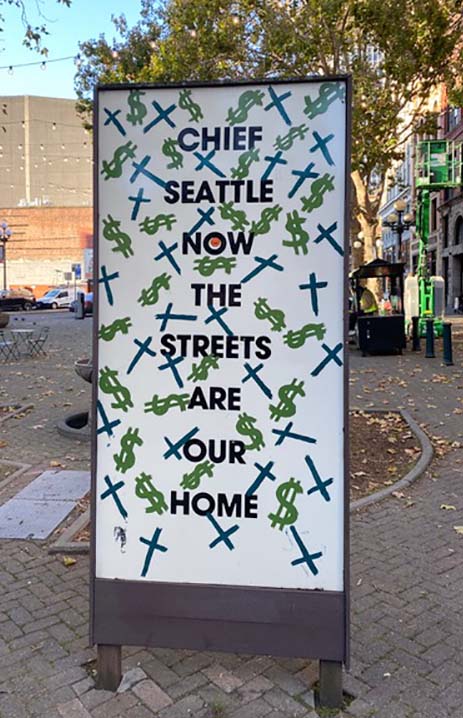

A poster in Pioneer Square in downtown Seattle brings this point home for Native Americans in stark, if seemingly mocking, terms to Chief Seattle, a great warrior and leader, who signed a peace and land treaty with the U.S. government in 1854.

As the poster suggests, a disproportionate number of Native Americans are living on Seattle’s streets in Seattle. Like Blacks, they are five times overrepresented among Seattle’s homeless compared to the general population.

(As a side note, today’s homeless situation can hardly be blamed on Chief Seattle, who in an impassioned speech to the U.S. government based his treaty agreement on the understanding of kind and protective treatment by the government.)

Homeless Individuals

People who become homeless are diverse, and no summary statement does justice to their uniqueness and individuality.

Still, it is clear that most share major commonalities.

People who are homeless have often been born into poverty (including people are second and third generation homelessness). Many suffer from serious health conditions, especially serious mental illness or substance abuse addictions. Education levels are lower and many lack high-level job skills.

Many have experienced multiple traumas—e.g., rape, physical abuse, death of a parent during childhood, disasters, and more—across their lives. They often don’t have close family. Some have made bad choices (at some point in life, haven’t we all?) and most have had bad luck.

And yet those characterizations are only part of the picture.

From nearly 40 years of working with hundreds of homeless clients, many with mental health and substance abuse problems, I know that homeless people are also individuals of strengths, worth, and resilience.

When treated with compassion and dignity, when served with understanding and patience, when offered resources and assistance, the vast majority of homeless people are eventually able to live healthier, happier lives as housed members of the community—and often with new, wiser perspectives.

Adam is one example of a person who dramatically changed from his previous homeless life, which was characterized by panhandling, sleeping in abandoned buildings, and attempting suicide at the command of schizophrenic voices. With the assertive community treatment mental health program, he was able over time to maintain a stable apartment, engage in volunteer work, and actively participate in a neighborhood church while dreaming of making even greater contributions to the lives of others. He was grateful for his services even as he urged others to also become “strong.” “That’s something everybody should understand, because we all only get one chance,” he said, “and we got to make the best of that, because if we don’t, what are we going to be?”

Another individual, Ann, lost her job of 18 years after she developed severe paranoid and delusional symptoms. She was unable to recognize her symptoms as mental illness and became suspicious and withdrawn. Eventually, she ran through her savings, lost her apartment, and became homeless. While homeless, she was sexually assaulted.

Ann initially refused help from anyone. But outreach workers continued to engage Ann, consistently offering help as well as friendship. After gaining her trust, the outreach workers helped her to obtain psychiatric medication, housing resources, and ongoing support services, and she was again able to live in her own apartment and to develop new friendships. For the first time in years, she felt good about herself, and planned to return to work or to volunteer activities.

Most telling, however, was the outlook on life that she developed. “Being homeless has given me a better perspective,” she said, reflecting back on her experiences. “It’s not just about how much money you have in a bank account, it’s about being open and caring.”

Photo by Matt Collamer

A Matter of Perspective and Values

Ultimately, the third and biggest reason that homelessness persists despite our ability to end it with affordable housing and effective services involves our perspective and values.

We are a nation of millions of good people, but we often act indifferent to the problem of people living and dying homeless.

Perhaps this is because too often we see homeless people as undeserving or a nuisance, instead of people of worth and potential.

Worst of all, we tend to act as if the homeless are so different from us, almost as if they were something less than full-fledged members of the human family. (Given a slightly different strand of DNA, one major life crisis, a bit of bad luck, it might be . . . There But for the Grace of God Go I.)

But we can choose a different perspective.

An important alternative comes from Chief Seattle who had the foresight to say to the U.S. government in his 1854 response to their treaty offer:

“We are all brothers after all.”

Chief Seattle was right.

We are all brothers and sisters.

We are all interconnected members of the human family.

And for a multitude of reasons, including religious beliefs (something especially relevant at Christmastime, given the values of Jesus), and for simple reasons of respecting our shared humanity, shouldn’t we treat all of our brothers and sisters with love and kindness?

Lead photo by Nick Fewings, Unsplash.com

Gary, reading your article on “A Time to End Homelessness” touches my Heart. I agree with all you shared concerning those who are homeless and it is time to end homelessness!! One of my cherished memories is my connection with Bill, a homeless man in downtown St. Louis. I had tried to help him trust my encouragement for him to let me take him to a shelter as it was getting colder and colder moving into Winter. I was so thankful that Bill, on a day with a below zero degree temperature, let me take him to a shelter. I was able to keep in contact with him and he did not become homeless again.

Thank you, Susan. The caring and connection you showed Bill made such a difference in ending his homelessness and improving his life–those actions of reaching out, developing trust, and caring are fundamental for helping people in so many ways, including ending homelessness.